Turning good manuscripts into great books.

Turning good manuscripts into great books.

My business motto sets a standard for my clients so they understand my editing style, including why I tend to be nit-picky about details many readers might not notice—my goal is to help create great books, not good ones.

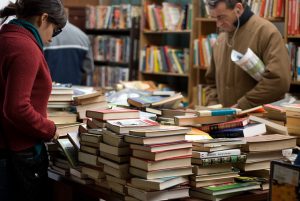

There are a lot of good books out there. They have decent plots, characters, and conflicts, but they’re largely forgettable. People read them and rate them 3- or 4-stars, but they never talk about them again. Or worse, they confuse them with someone else’s book and talk about the wrong one!

So, what is it that boosts a book into greatness?

- Attention to detail.

- Honing the writing craft.

- Doing what’s best when other writers do what’s easiest.

- Time.

Here’s the hard truth: Well-established authors can get away with breaking the “rules” because they already have a fan base. Their fans will forgive them if their latest plot isn’t quite as engaging or the characters quite as unique. For new writers, however, the standard is higher—they need to develop that fan base, that tribe, first, and that means writing to that higher standard.

Unfortunately, meeting that standard almost always means years of writing, learning, and revising, and many authors aren’t interested in investing that much time. They want to get their books out as quickly as possible, so they publish a good book instead of waiting to make it a great one.

I’ve told many writers that their manuscripts are good, even admitting that I’ve read some published books at the same level as their manuscripts. But I don’t turn them away and wish them luck with a good book; I ask them if they want to work harder to produce a great one. It takes time and a lot of work, but the result is always a better book. It’s a book that sticks with people, that they share with others because it captured their hearts.

If you’d like to see if your good manuscript can be better, leave a comment or contact me at karin@writenowedits.com.

For more fiction-writing tips and advice, follow me on Facebook at Writing Now Editing, or sign up for my monthly newsletter and learn the easiest way to make a good impression with agents and publishers!